The Maga, Murder, and Immanuel Kant: Thomas De Quincey and the Advocates Library

A plaque attached to No. 6 Gloucester Place, Edinburgh commemorates former resident ‘Christopher North’.

Gloucester Place is an attractive Georgian terrace at the northern edge of the New Town just before the streets drop down to Stockbridge. It’s the sort of street that makes me wish for a large lottery win. At No. 6 is a chic boutique hotel with a restaurant and bar called ‘Blackwoods’. A verdigris plaque affixed to the silver-hued stone announces that this was once the home of ‘Christopher North’.

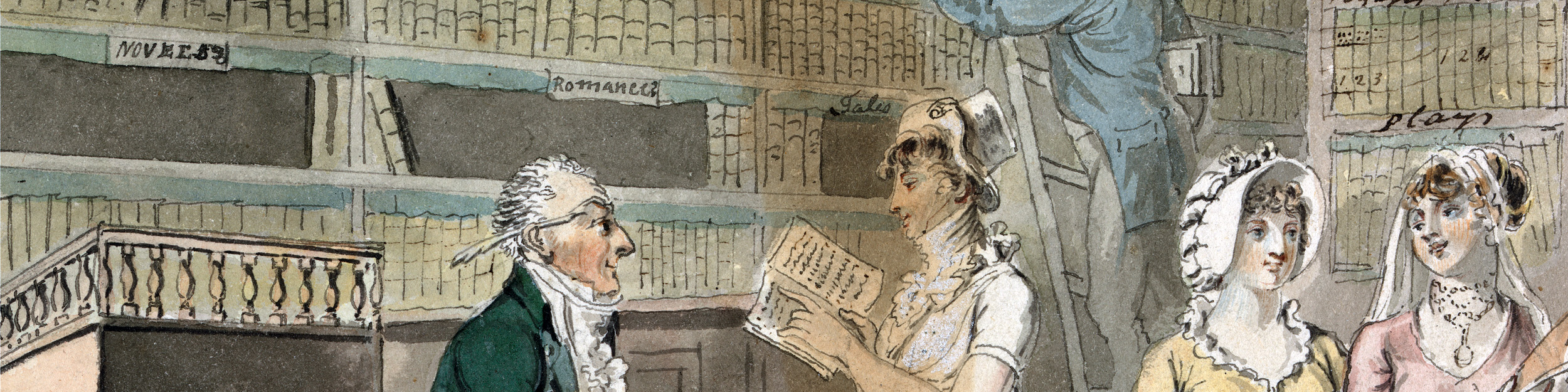

Christopher North, whose real name was John Wilson, was one the most prolific of contributors to and editor of Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine. Alongside his publications in Blackwood’s, he published a collection of essays called Lights and Shadows of Scottish Life (1822) and the novels The Trials of Margaret Lyndsay (1823) and The Foresters (1825).[1] These were especially popular with Chambers’ Circulating Library borrowers, as was the ‘Maga’ as Blackwood’s was known.

Blackwoods Hotel and Restaurant, Edinburgh

Wilson was a long-time friend – and sometimes perceived enemy – of Thomas De Quincey. They had met in 1808 when they were both living in the Lake District to be near William Wordsworth. In September 1826, De Quincey moved to Edinburgh and took up residence in Gloucester Place.[2]

Thomas De Quincey, 1785-1859. Author and essayist. by Sir John Watson Gordon (1846). Scottish National Galleries PG 553 (Creative Commons CC by NC)

De Quincey was in a perilous financial state, a regular occurrence with him, so turned to his old friend seeking journalistic work. Blackwood’s, with its critical essays and reviews, was one of the most influential arbiters of taste in its age and the perfect place for De Quincey’s talents. He had published in the Maga before with ‘The Sport of Fortune’ in 1821 and publisher William Blackwood noted with some surprise in 1826 that De Quincey had arrived at an Edinburgh dinner party and was in town ‘expressly to write articles for the Magazine’.[3] De Quincey was a skilled essay writer and translator and famous – or notorious – for his drug memoir Confessions of an English Opium-Eater of 1821 in the London Magazine which appeared in book form the following year. He had appeared in fictionally as the ‘English Opium-Eater’ in Blackwood’s ‘Noctes Ambrosianae’, a long-running series of imaginary literary and political discussions led by Christopher North and held by the denizens of Ambrose’s Tavern, including James Hogg as the ‘Ettrick Shepherd’.

De Quincey as a Borrower in the Books & Borrowing Database

On 23 December 1826, two books in German were borrowed from the Advocates Library marked ‘De Quincey’. These were the first volume of Immanuel Kant’s Biographie (1804) attributed to Georg Samuel Albert Mellin [NLS Jac.V.3.28] and ‘Borowsti [sic] 12mo’. The Borowski reference relates to three books on Kant that were bound together as they currently are in the National Library of Scotland and were almost certainly so in the Advocates Library at the time De Quincey had access to them. They are:

- Ludwig Ernst Borowski, Darstellung des Lebens und Charakters Immanuel Kants (1804) [NLS Jac.V.3/1(1)]

- Reinhold Bernhard Jachmann, Immanuel Kant geschildert, in Briefen an einen Freund von Reinhold Bernhard Jachmann (1804) [NLS Jac.V.3/1(2)]

- Ehregott Andreas Christoph Wasianski, Immanuel Kant in seinen letzten Lebensjahren (1804) [NLS Jac.V.3/1(3)]

All three were published in Königsberg by Friedrich Nicolovius. The ‘Jac.V’ shelfmarks indicate that the books were once shelved in the Advocates Library’s ‘Regal Room’ which featured shelfmarks named for seven early Scottish kings. Some are still used today.[4]

FR 263, f. 163: Books on one of George Brodie’s Advocates Library borrowing pages borrowed 23 December 1826 and marked ‘De Quincey’.

The German books were borrowed under the aegis of the advocate and historian George Brodie. Quite how De Quincey knew Brodie is as yet unknown. Brodie seems to have acted as a factor non-advocates to access the Advocates Library. On the same page as the books identified as for De Quincey are loans by Brodie on behalf of Dr Russell and Dr Irving. Brodie borrowed heavily from the Advocates Library. The Books and Borrowing database so far contains 197 borrowings by him dating from 1819 to 1830. Most of these demonstrate his own interest in seventeenth-century history. His History of the British Empire from the Accession of Charles the First to the Restoration published in four volumes in 1822 demonstrates his whiggish perspective to history.[5] This put him at adds with the authors associated with the Maga which had been founded to counter the whiggish Edinburgh Review.[6] The loans show – as we are often finding in the Books and Borrowing project – that libraries with seemingly strict rules about access did allow borrowing beyond their official strictures.

De Quincey and Blackwood’s, November 1826 – February 1827

The February 1827 issue of Blackwood’s contained the first of De Quincey’s famous essays on the art of murder, ‘On Murder considered as one of the Fine Arts’ began with a letter purported to be from one ‘XYZ’ and reported on the activities of ‘The Society of Connoisseurs in Murder’ which monitored police annals to find murders to critique and met in secret to share its findings.[7] A lecture with plenty of dark humour supposed to have been presented to the society followed. Philosophers feature heavily with some falling victim to practitioners of the art of killing.

NOT the victim of a murderous artist. German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724-1804) by Johann Gottlieb Becker (1768). https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Kant_gemaelde_3.jpg

Immanuel Kant appears twice. He is ‘a great moralist of Germany’ who would help a murderer find an escaped potential victim.[8] This was because for Kant all telling of lies was wrong. Later in the lecture, Kant himself avoids being murdered when a murderer lying in wait for him ‘preferred a little child, whom he saw playing in the road, to the old transcendentalist’.[9] This murderer was ‘an amateur, who felt how little would be gained to the cause of good taste by murdering an old, arid, and adust metaphysician…who could not possibly look more like a mummy when dead, than he had done alive’.[10] The story came from ‘an anonymous life of this very great man’.[11]

De Quincey embarked on a series of essays for a ‘Gallery of German Prose Classics. By the English Opium-Eater’ upon arrival in Edinburgh. Blackwood’s for November 1826 saw a first essay on Gotthold Ephraim Lessing; a second followed in January 1827. Immanuel Kant was the subject of De Quincey’s February 1827 contribution to the series as ‘The Last Days of Kant. From the German of Wasianski, Jachmann, Borowski, and Others’. Remember those borrowings from the Advocates Library, mentioned above? The authors mentioned look look rather familiar. De Quincey’s commitment to popularising German literature was further demonstrated by at glowing anonymous review for his friend Robert Gillies’s German Stories in the December 1826 issue.[12]

Title heading for ‘The Last Days of Kant. From the German of Wasianski, Jachmann, Borowski, and Others’, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, February 1827.

Whether De Quincey accessed other libraries in Edinburgh is as yet known. He could have perhaps borrowed books via John Wilson who was both an advocate and Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Edinburgh from 1820 to 1851. (His borrowing pages from both institutions are not yet transcribed.) We may never know what connections De Quincey made and what books may have been borrowed on his behalf during his many years in Edinburgh. He made many friends and had many things to write about. The borrowings of 23 December 1826 show that such borrowings did occur and that they can be linked directly to topics De Quincey was writing about for the Maga.

De Quincey remained in Edinburgh, writing prolifically on a range of subjects, evading debt collectors, and continuing his addiction to opium for most of the rest of his life. He died on 8 December 1859 and was buried in St Cuthbert’s kirkyard.

[1] David Finkelstein, ‘Wilson, John [pseud. Christopher North] (1785–1854), author and journalist’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23 September 2004), https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-29668 <accessed 28 November 2023).

[2] Frances Wilson, Guilty Thing: A Life of Thomas De Quincey (New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016), p. 256.

[3] Quoted in The Works of Thomas De Quincey, vol. 6: Articles from the Edinburgh Evening Post, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine and the Edinburgh Literary Gazette, 1826-1829, ed. by David Groves and Grevel Lindop (Oxford: OUP, 2000; Oxford Scholarly Editions Online, October 2018), p. 26. 10.1093/actrade/9781138764873.book.1 <accessed 29 November 2023).

[4] See ‘Advocates Library Shelfmarks’, https://www.nls.uk/collections/rare-books/collections/advocates/shelfmarks/. This has been immensely helpful in matching transcribed records in the Books and Borrowing database to surviving books in both the Advocates Library and the NLS.

[5] Francis Espinasse and H. C. G. Matthew, ‘Brodie, George (1785–1867), historian’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (23 September 2004), https://www.oxforddnb.com/view/10.1093/ref:odnb/9780198614128.001.0001/odnb-9780198614128-e-3487 <accessed 28 November 2023>.

[6] For a very brief introduction to periodicals in the time covered by Books and Borrowing, see our online exhibition with the University of Edinburgh: https://exhibitions.ed.ac.uk/exhibitions/library-lives/edinburghs-reading-lives.

[7] Thomas De Quincey, ‘On Murder Considered as one of the Fine Arts’, Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine, 21 (Feb. 1827), p. 199. For more on De Quincey’s essays on murder see, Sarah Sharp, ‘A Club of “Murder-Fanciers”: Thomas De Quincey’s Essays “On Murder” and Consuming Violence in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine,’ Nineteenth-Century Contexts (26 October 2023), https://doi.org/10.1080/08905495.2023.2273081 <accessed 28 November 2023>.

[8] Ibid., p. 200.

[9] Ibid., p. 208.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Works, 3.