A year at Westerkirk

Westerkirk and Langholm in a detail from John Ainslie, The environs of Edinburgh, Haddington, Dunse, Kelso, Jedburgh, Hawick, Selkirk, Peebles, Langholm and Annan (1812). Courtesy of National Library of Scotland.

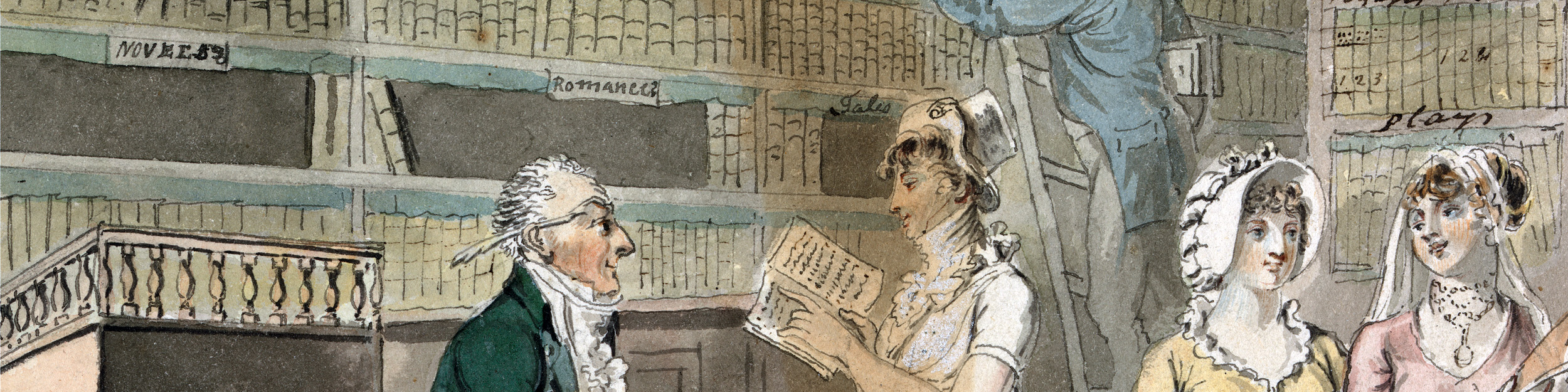

Back in July, I wrote about my trip to the evocative Westerkirk Parish Library in Dumfriesshire to photograph materials for the Books and Borrowing project. The process of adding records from the library’s manuscript borrowing register (styled the ‘Kalendar’ by its users) into the database is now well underway, and I recently passed a minor milestone, having entered a year’s worth of borrowings into the system. The ‘Kalendar’ starts in 1813, and if that year is anything to go by, Westerkirk represents a significant addition to our overall dataset. So far we have 1339 borrowings, 230 titles and 79 active borrowers (around 90 individual members are named in all), four of them women.

Page from the Westerkirk ‘Kalendar’. Courtesy of Westerkirk Parish Library.

Working with any manuscript material has its rewards and challenges, but Westerkirk’s relatively rigid format for recording borrowings—essentially a spreadsheet with borrowers down the side and months along the top (in that sense the volume really is a ‘Kalendar’)—is already pretty amenable to the data structure of a digital project. A slight complication arises from the Westerkirk librarians’ practice of giving catalogue numbers rather titles to record borrowings. The downside to this is frequent detours via the historic catalogue to identify what books are being borrowed by matching numbers to titles. However there’s also a major upside, in that this way of doing things largely eliminates problems of identification caused by ambiguous or incomplete titles in borrowing records, such as ‘Sermons’ or ‘Plays’. It’s also rewarding to see the rows of numbers in the ‘Kalendar’ turn into recognisable book titles, and start to get a rough sense of what was being borrowed, something not immediately visible from a quick browse of the manuscript page, and a reminder of some of the inherent advantages of a digital approach.

When I originally wrote about visiting Westerkirk, I wondered whether any of the members mentioned in the minutes of the miners’ library in the 1790s would pop-up in the later borrowing records, and whether the library’s nineteenth-century members would make much use of those donated books that formed the original collection. The answer to the first question seems to be a resounding yes, even accounting for the possibility of shared first and last names. It will be interesting to dig a bit deeper on those individuals at some point, and find out more about their stories. As for the books, some, such as Matthew Hale’s Contemplations do appear in the borrowings for 1813, though so far these (generally older) works seem less popular than the library’s later additions.

Jane Porter, author of Scottish Chiefs

And the rest of the borrowings? Of course, the evidence of a single year isn’t enough to pick-out larger patterns and trends, but there are some clear favourites for 1813, including Jane Porter’s historical novel The Scottish Chiefs, and William Fordyce Mavor’s travel anthology, The British Tourists. Other, less frequently borrowed works nonetheless hint at the local interests represented in the library’s collection, such as the works of the relatively obscure Border poet, James Ruickbie. As the project continues, it will be interesting to see if and how the preferences of the Westerkirk borrowers shift with time, and whether they align with or diverge from the broader picture of Scottish borrowing habits in this period.