Anatomy of a Holding: Robert Burns at the Wigtown Subscription Library

The accounts of the Wigtown Subscription Library in Galloway register a payment of one pound, eleven shillings and sixpence for ‘Burns’s works’ on 22 October 1800, followed by a payment of sixpence for ‘Carriage from Dumfries’ five days later.[1] Cross-reference to the library’s borrowing registers reveal that this text was in four volumes, confirming it as the first edition of James Currie’s newly published Works of Robert Burns; with an account of his life, and a criticism on his writings; To which are prefixed, some observations on the character and condition of the Scottish peasantry.

This edition was, for Leith Davis, ‘the most important work determining Burns’s cultural currency during the romantic era’.[2] It represented a major step forward in the literary canonisation of the poet, not least because it included a large portion of his correspondence as well as Currie’s long biographical essay in its elegant presentation set, helping to establish a particular and enduring emphasis on Burns’s private life in the cult of the national poet. It became and remains controversial, however, because of Currie’s professional view that Burns was an alcoholic, generating what Nigel Leask calls a pervasive ‘rhetoric of moral blame’ – Currie, though originally from Dumfriesshire, was a successful physician as well as liberal intellectual in Liverpool.[3]

Currie’s edition, then, would be instrumental in the evolving celebration of Burns that continues today around the anniversary of his birthday. And in truth the trajectory that would lead to Burns clubs (the first, in Irvine, founded 1826) and the enduring traditions of haggis and recital was a related expression of the associational culture and institutionalised patriotism underpinning the Wigtown library itself, founded just five years earlier. The 1786 (Kilmarnock) and 1787 (Edinburgh) editions of Burns’s Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect had both been published by subscription – the latter, particularly, with its ostentatious list of names, manifested a kind of polite pseudo-institution in its pages. Currie’s edition was a paternalistic variation on this, since, in the wake of Burns’s death in 1796, it was explicitly directed at raising money for the poet’s family.

In this light, and especially given the regional proximity of Wigtown and Dumfries, it is no surprise to find the Wigtown subscribers snapping up Currie’s edition at the first opportunity. However, the library’s borrowing ledgers complicate the picture. In the surviving nineteenth-century records we have analysed (1828-1836) the text is borrowed on only eleven occasions (twenty-two if we count each volume taken), a surprisingly poor performance, relatively speaking, for such an ostensibly important holding. As a point of comparison, while Currie’s edition appears to have been the only Burns possessed by Wigtown, they had forty-one separate works by Walter Scott, which were cumulatively borrowed 1031 times in the same period.

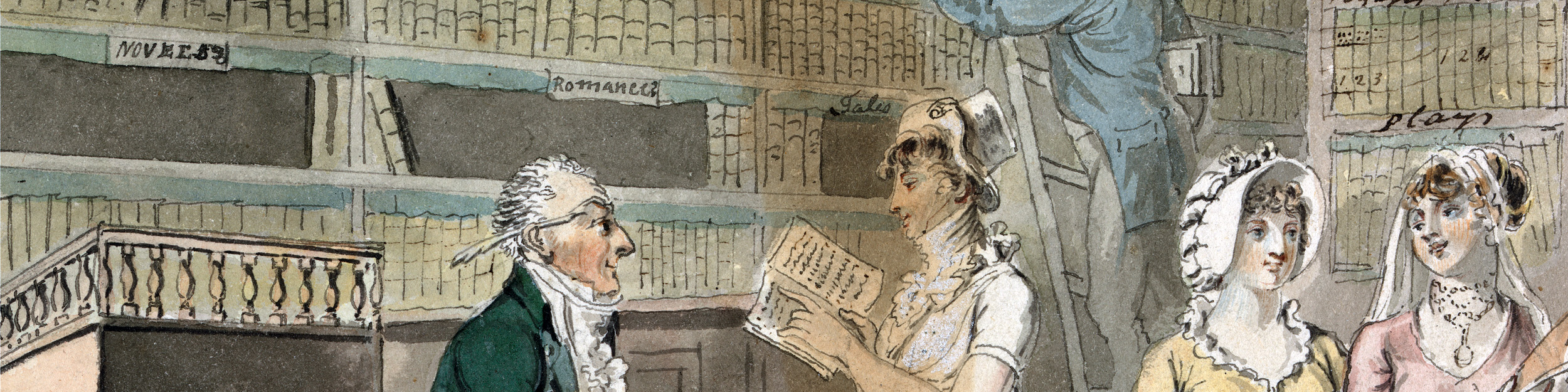

Two 1830 borrowings of Currie’s Burns sandwiched between Walter Scott and James Hogg. Broughton House MSS 11/29, page 170.

There are a few possible explanations, the first and most obvious being that the enormous gap in the archival record between 1800 and 1828 is likely to have contained the peak years of the edition’s novelty. At the same time, the Wigtown subscribers by the late 1820s may have had access to their own, cheaper editions of Burns. Leask describes Currie’s edition as ‘the main portal through which Burns’s life and poetry reached the Romantic and nineteenth-century reader’, but that underestimates its daunting price tag.[4] It would have been out of reach for most of the reading nation, for whom alternatives such as the pirated chapbooks and affordable editions produced in Glasgow by Stewart and Meikle from 1799 were more realistic. One of the fundamental aims of subscription libraries, of course, was to enable access to expensive books by pooling resources amongst a group of subscribers, as was the case here. Still, that would not preclude subscribers from picking up less precious editions for their home shelves, assuming that they were in fact interested in Burns’s oeuvre.

Despite the limited borrowing of Currie’s Burns by the turn of the 1830s at Wigtown, there were other reasons for having an expensive edition of the new national poet in the library, aside from actually reading it. The assembly of this collection was certainly motivated by the practical desires of subscribers for reading material, but it also represented a statement of cultural identity, such that the four volumes of the Works of Robert Burns were an essential signifier of Wigtown’s polite and patriotic credentials.

[1] Broughton House, Kirkcudbright, MS 5.27, 96.

[2] Leith Davis, ‘James Currie’s Works of Robert Burns: The Politics of Hypochondriasis’, Studies in Romanticism 36.1 (1997): 43–60, (43).

[3] Nigel Leask, Robert Burns and Pastoral: Poetry and Improvement in Late Eighteenth-Century Scotland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), 281.

[4] Ibid., 276.