Jane Porter and the Historical Novel before Waverley

“The war which had desolated Scotland was now at an end. Ambition seemed satiated; and the vanquished, after passing under the yoke of their enemy, concluded they might wear their chains in peace. Such were the hopes of those Scottish noblemen who, early in the spring of 1296, signed the bond of submission to a ruthless conqueror; purchasing life at the price of all that makes life estimable—Liberty and Honour.”

Jane Porter, The Scottish Chiefs: A Romance, 5 vols. (1810).[1]

Jane Porter by George Henry Harlow, pencil, 1800s. NPG 1108

© National Portrait Gallery, London

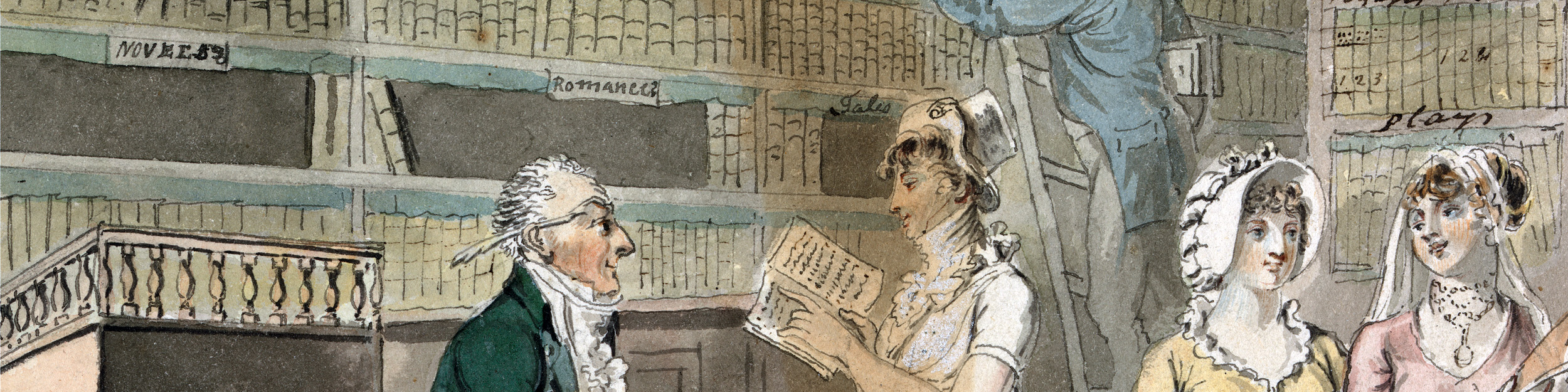

For some, the Coronavirus lockdowns of the past year have provided the perfect excuse to revisit the so-called “Golden Age of Television” by binge-streaming those acclaimed series that that we missed first time round, or had always planned to grace with a second watch. Others take a type of stubborn pride in having spent the last twenty years managing to resist the pressure to sit down in front of The Wire or The Sopranos, and are loath to surrender now. The latter mentality might have been admired by the early-nineteenth-century membership of Westerkirk Library, who (as far as I can tell) successfully avoided adding Walter Scott’s Waverley (1814) and its sequels to their collection until the mid-1820s. As Gerard McKeever wrote last week, Scott’s historical novels had a transformative impact on the period’s literary marketplace and culture, one which was reflected in the borrowing and buying habits of libraries. But it’s also long been acknowledged that Scott’s status as originator of the historical novel rests on contended ground. Four years before the appearance of Waverley, Jane Porter’s five-volume novel The Scottish Chiefs: A Romance (1810), revealed the widespread appetite for fictionalised accounts of Scotland’s past. At Westerkirk library, Porter’s novel was borrowed over 160 times between 1813 and 1816, making it by far the collection’s most borrowed novel for that period, and second most popular holding overall, trailing The Edinburgh Encyclopaedia by eight borrowings.

Another take on the historical sublime: Sir Robert Ker Porter, ‘An Ancient Castle’ (c.1799-1800) http://www.tate.org.uk/art/work/T08532

Born in the north of England and educated in Scotland, Jane Porter’s siblings included fellow novelist Anna Maria and the artist Sir Robert Ker Porter. Jane Porter first found literary success with Thaddeus of Warsaw (1803), a fictionalised account of a refugee from the occupation of Poland in the 1790s. For The Scottish Chiefs, Porter looked both closer to home and further back in time, presenting a sprawling account of the wars of Scottish Independence and the tribulations of its heroes, William Wallace and Robert the Bruce, although the novel’s most compelling figure turns out to be Wallace’s unrequited admirer, Helen, Lady Mar.

Like Scott’s Waverley, Scottish Chiefs capitalised on the contemporary vogue for Highland tourism, with descriptions of sublime and picturesque scenery providing a constant backdrop to the actions of its characters, historical and invented. The Scottish Chiefs anticipated the dominion Scott’s historical novels would hold over early-nineteenth century prose fiction, but also drew on the well-established cultural forms of gothic romance, sentimentalism, and evangelical moralism, not to mention the ballad tradition from which the modern conception of Wallace is still largely drawn. The novel opens with Wallace living the life of a pious hermit who bears a more than passing resemblance to the heroes of James Macpherson’s Ossian:

Cover of a 1950 comic-book adaptation of Porter’s novel. Internet Archive.

“The hunting-spear, with which he delighted to follow the flying roe-buck from glade to glade, from mountain to mountain; the arrows with which he used to bring down the heavy termagant or the towering eagle, all were laid aside (…) books, his harp, and the sweet converse of his tender Marion, were the occupations of his days.”[2]

To follow Ian Duncan’s influential account in Scott’s Shadow, Porter’s enthusiastic vision of history as romance is precisely what was purged from the genre by the Humean scepticism of Waverley —partly because it carried a whiff of fanaticism, whether religious, Jacobitical, or Jacobin.[3] Yet as Fiona Price points out in a useful article on Porter’s historical fiction, Wallace’s patriotic pursuit of ‘Liberty’ in The Scottish Chiefs, although superficially rebellious, easily lent itself to the anti-Napoleonic rhetoric of wartime Britain (tellingly, the French translation of the novel was proscribed by Napoleon).[4] Ultimately, any political reading is tempered by the use of Wallace’s tragic fate to deliver the typically evangelical message that true freedom and contentment are only found in Heaven.

There is undoubtedly a story behind Westerkirk’s apparent resistance to Waverley, but in the meantime, we can only speculate as to why the library was apparently so late to Scott’s historical fiction, while at the same time showing such keenness for Porter’s. In the meantime, this case serves as a reminder that libraries were anything but straightforward channels between literary production and contemporary readers. It’s also adjusted my perspective on Scott’s significance, and the alternative approaches to historical fiction that have been overshadowed by the cultural juggernaut of Waverley.

[1]Jane Porter, The Scottish Chiefs; A Romance […] Five Volumes in Two (Hartford: 1822), 2 vols., i, p.5.

[2] Ibid, p.6.

[3] Ian Duncan, Scott’s Shadow: The Novel in Romantic Edinburgh (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007), p.29.

[4] Fiona Price, ‘Resisting ‘the spirit of innovation’: The Other Historical Novel and Jane Porter’, The Modern Language Review, 101:3 (2006), pp.638-651, 651.