Thomas Jefferson and the ‘extensive good’ of the Subscription Library

As regular readers of the Books and Borrowing blog will know, I spent three months of my summer as a visiting scholar at the International Center for Jefferson Studies (ICJS) at Monticello, kindly funded by the Scottish Graduate School for Arts and Humanities. During my time in the United States, I was fortunate enough to be able to visit and access the records of subscription libraries in Charleston, New York and Philadelphia, each of which I blogged about. The rest of my time in the US was spent in the peaceful confines of the Jefferson Library at the ICJS, and within a friendly and intellectually stimulating environment of scholars, fellows and librarians.

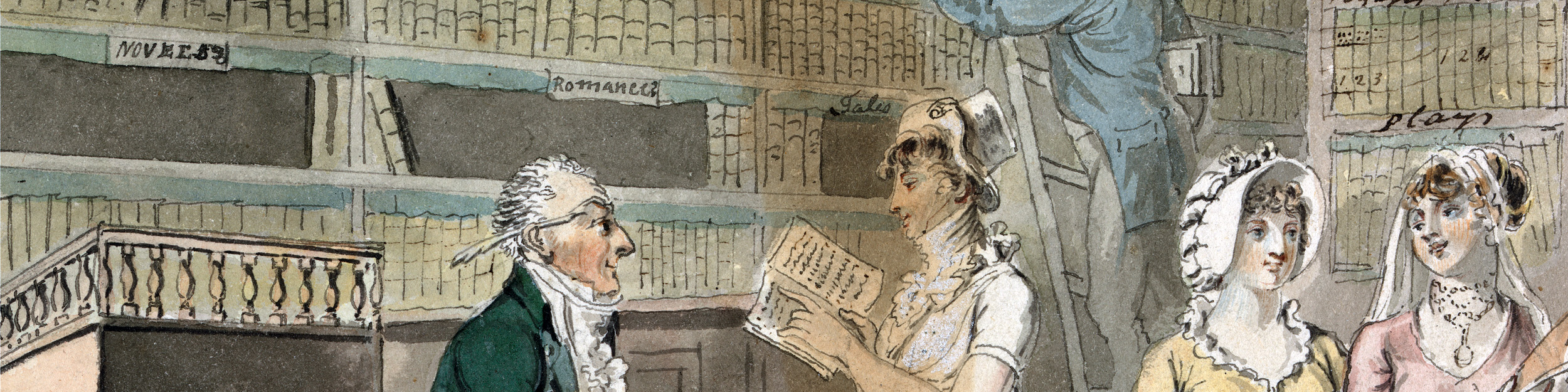

Although they are thoroughly Scottish libraries, the type of library association of the Haddington, Leighton, Orkney, Selkirk, Westerkirk and Wigtown libraries, the subscription library, was partly a North American invention. The first proprietary subscription library, was the Library Company of Philadelphia, founded in 1731 by a group of fifty shareholders, of which included Benjamin Franklin.[1] In North America, as they were in Scotland, such libraries regularly involved the cooperation of members of the aristocratic and middling orders in the founding, patronage and maintenance of these libraries.[2] In rural Virginia, Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826) played the role of an aristocratic patron, having little personal need for a local subscription library, but eager to offer his support, both financial and administrative, in their emergence and success.

The author of the Declaration of Independence and the third president of the United States, Thomas Jefferson’s love of books and reading is intimately associated with his character and politics. Jefferson regularly voiced his desire to retire from active politics and return to the quiet and seclusion of his mountaintop home at Monticello. His craving to be back amongst his books formed a major aspect of this: ‘My books, my family, my friends, and my farm, furnish more than enough to occupy me the remainder of my life’.[3] It is estimated that Jefferson owned between 9,000 and 10,000 books during the course of his lifetime.[4] He bought new publications on a regular basis and self-diagnosed himself as suffering ‘under the malady of Bibliomanie’, an inability to stop purchasing new books.[5]

Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), ‘The Edgehill Portrait’, by Gilbert Stuart. © National Portrait Gallery, Washington D.C.

Despite Jefferson’s famous proclivity for books and libraries, his connection with and views of the subscription library have been relatively under-examined, even by those studies expressly concerned with assessing his life through books. Although he had little need for such libraries himself, Jefferson wrote warmly for and actively supported the founding of these libraries in his native Virginia and was involved in the formation of at least two subscription libraries in the state in the years following his presidency. These were the Westwardmill Library Society (founded 1808), in Brunswick County, and the Albemarle Library Society (founded 1823), located in Charlottesville. In the case of both libraries, Jefferson was asked to comment on their proposed rules and constitution and sent each a list of books he recommended them to purchase.[6]

In correspondence with a founding member of the Westwardmill Library Society, Jefferson was effusive in his praise for the subscription library as a general form of library association:

‘I have often thought that nothing would do more extensive good at small expence than the establishment of a small circulating library in every county to consist of a few well chosen books, to be lent to the people of the county under such regulations as would secure their safe return in due time… should your example lead to this, it will do great good’.[7]

Whilst this passage has been regularly quoted, shorn of its original context it can be easily misunderstood. Jefferson is referring to neither a truly public library nor a commercial circulating library.[8] The library capable of the most ‘extensive good’ is the subscription library, autonomous and collectively managed library societies, like the Westwardmill Library Society, which were not open to the general public but only their paying subscribers.

Albemarle County Circuit Court in Court Square, Charlottesville, Virginia. The first home of the Albemarle Library Society was at No. 2, on the right-hand side of this square.

Jefferson played a larger role in the founding of Charlottesville’s subscription library, the Albemarle Library Society in 1822, being a supporter of it from its outset. He purchased four shares in the library, at a cost of $10 each, and seems to have served on a committee to prepare a catalogue of books to purchase.[9] Whilst Jefferson would have had little need to use the library himself, it’s clear that the library was used by the community. The local lawyer and freemason, Valentine Wood Southall (1793-1861) served as the society’s first president, whilst a list of borrowers fined for overdue books lists some of Charlottesville’s prominent citizens, including members of the Meriwether and Garrett families.[10] Rather astoundingly, these two pages of those fined for overdue books, possibly the library’s only surviving manuscript records, reveals that no leniency was offered to the library’s administrators, with the library’s secretary, treasurer and librarian all fined for the late return of books. Indeed, one of those fined was the library’s treasurer, William Wertenbaker (1797-1882), who would later be appointed the University of Virginia’s second librarian in January 1826.[11]

For those who chose to join it, the Albemarle Library Society represented an opportunity to associate themselves with Charlottesville’s leading citizens. It therefore had a political significance in an age in which politics and civic business revolved around social connections forged in private and semi-public spaces. For his own part, Jefferson recognised this political significance through the intellectual and educational merits of these libraries:

the people of every country are the only safe guardians of their own rights and are the only instruments which can be used for their destruction. and certainly they would never consent to be so used were they not decieved.[12]

In Jefferson’s eyes, subscription library members and a sufficiently educated citizenry would be one better placed to guard against demagogues, tyranny and the potential abuses of executive power.[13]

Selection of books from the Albemarle Library Society now at the University of Virginia Library.

[1] J.A. Leo Lemay, The Life of Benjamin Franklin, Volume 2: Printer and Publisher, 1730-1747 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), pp.93-123; “At the Instance of Benjamin Franklin”: A Brief History of the Library Company of Philadelphia, rev. ed. (Philadelphia: The Library Company of Philadelphia, 2015), pp.5-11.

[2] Mark Towsey, ‘First Steps in Associational Reading: Book Use and Sociability at the Wigtown Subscription Library 1795–99’, Papers of the Bibliographical Society of America, 103.4 (2009), pp.455–95.

[3] Thomas Jefferson to Pierre Auguste Adet, 14 October 1795, Papers of Thomas Jefferson, 28, pp.503-04, quoted in Kevin J. Hayes, The Road to Monticello: The Life and Mind of Thomas Jefferson (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), p.352.

[4] Endrina Tay, ‘Thomas Jefferson and Books’, in Encyclopedia Virginia (2014), <https://encyclopediavirginia.org/entries/jefferson-thomas-and-books/>, [accessed 05/10/23].

[5] “Thomas Jefferson to Lucy Ludwell Paradise, 1 June 1789,” Founders Online, National Archives, <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/01-15-02-0166>,[accessed 05/10/23]. See also Hayes, Road to Monticello, p.314.

[6] “John Wyche to Thomas Jefferson, 19 March 1809,” Founders Online, National Archives, <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-01-02-0051>, [accessed 12/09/23]; “Thomas Jefferson to Frederick Winslow Hatch, 22 April 1823,” Founders Online, National Archives, <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-3473>, [accessed 12/09/23]. For these lists, see “Enclosure: Thomas Jefferson’s List of Recommended Books, [ca. 4 October 1809],” Founders Online, National Archives, <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-01-02-0453-0002>, [accessed 05/10/23]; “Albemarle Co., Va., Library Society: Catalogue of Books, 5 Apr. 1823, 5 April 1823,” Founders Online, National Archives, <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/98-01-02-3434>, [accessed 12/09/23].

[7] “Thomas Jefferson to John Wyche, 19 May 1809,” Founders Online, National Archives, <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/03-01-02-0170>, [accessed 12/09/23].

[8] For example, Robert C. Baron, ‘Introduction’, in The Libraries, Leadership, & Legacy of John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, Robert C. Baron and Conrad Edick Wright, eds. (Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing, 2010), p.xvii; Hayes, Road to Monticello, p.142.

[9] “Memorandum Books, 1823,” Founders Online, National Archives, <https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Jefferson/02-02-02-0033>, [accessed 12/09/23]; Edgar Woods, Albemarle County in Virginia (Charlottesville: The Michie Company, 1901), p.103.

[10] Andrew J. O’Shaughnessy, The Illimitable Freedom of the Human Mind: Thomas Jefferson’s Idea of a University (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2021), p.86; Albemarle Charlottesville Historical Society, MS 348, Jefferson-Madison Regional Library, Historical Documents, list of library fines, 1825-26.

[11] Harry Clemons, The University of Virginia Library, 1825-1950: Story of a Jeffersonian Foundation (Charlottesville: University of Virginia Library, 1954), pp.93-95; O’Shaughnessy, Illimitable Freedom, p.129.

[12] Jefferson to Wyche, 19 May 1809.

[13] O’Shaughnessy, Illimitable Freedom, p.4.