Event Report: Books and Borrowing in Eighteenth-Century Glasgow

We had the pleasure of running an event in Glasgow University Library Special Collections last week. This was an opportunity for us to share some of the research we have done specifically on the university’s own records, while bringing together colleagues with cognate interests to think more expansively about the Glasgow context and about the study of borrowing records. As this event made clear, borrowing records remain an under-explored resource with huge future potential.

Following some introductory remarks, the day main portion of the day was a series of talks from experts based at Glasgow. Dr Craig Lamont set the scene with an overview of Glasgow and its transformation from a fairly modest settlement (12,000 people c.1700) to a major imperial city over the course of the eighteenth century. Dr Lamont paid particular attention to the city’s role as a hub of Enlightenment culture, developing insights from his recent monograph The Cultural Memory of Georgian Glasgow (EUP, 2021).

This was followed by our own team members, Drs Matthew Sangster and Kit Baston, who provided the centrepiece for the day in terms of disseminating project research, in back-to-back talks unpacking their work on the Glasgow records 1757-1771: for more on this including links to the data itself see https://borrowing.stir.ac.uk/glasgow-student-borrowers/.[1]

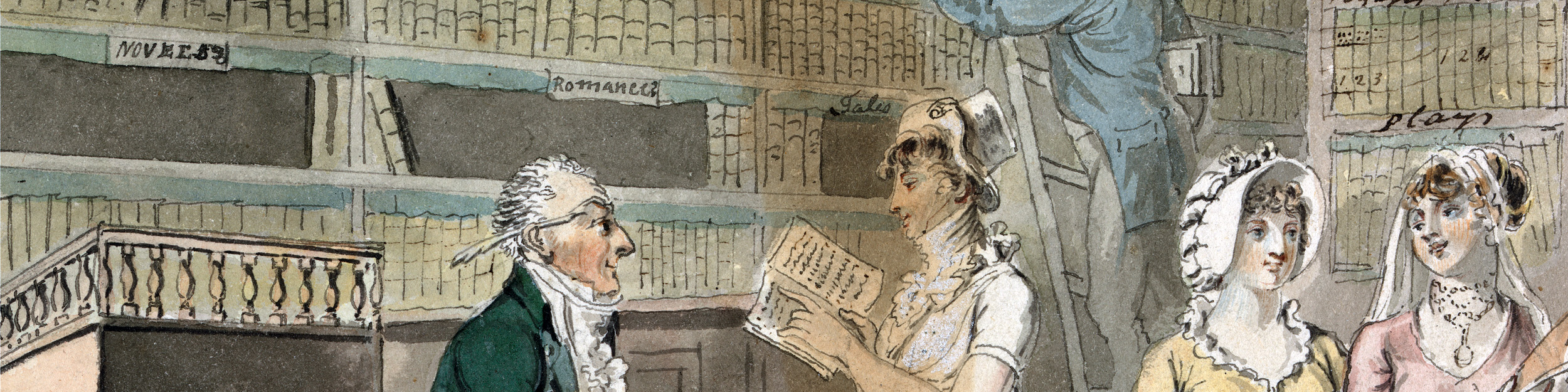

A slide from the talk given by Baston and Sangster.

Next, Robert MacLean gave us a perspective from inside GUL Archives and Special Collections. He noted, for example, that since not all students matriculated or graduated in the period, our analysis of borrowing records provides a rare documentation of individuals’ presence at the university, with real value to genealogical enquiries. He also described the c.400 volumes of (largely uncatalogued) library records held by Glasgow, which is both an exciting and terrifying prospect!

With these various contexts established, the talks then moved onto more topical enquiries. Dr Craig Smith, who was speaking via video-link from Baltimore, used the student borrowings at Glasgow to reconstruct elements of Adam Smith’s lectures that have previously been thought entirely lost to history. By observing distinctive borrowing patterns by students under Adam Smith at the relevant times of year, Dr Smith was able to sketch out the general tenor of his namesake’s approach to both natural theology and moral philosophy in these ‘missing’ lectures, demonstrating the creative potential of borrowing records when aligned with specific expertise.

Dr Craig Smith addressing the event via video-link.

The next talk was given by Dr Michelle Craig, who adapted her recent doctoral research on William Hunter to discuss the borrowing records of Hunter’s private library in London, which was subsequently removed to Glasgow. Dr Craig illustrated a strong sense of an intimate network in and around Hunter’s private borrowing register, providing an example of the intellectual communities we find manifested by reading (or at least borrowing) in the period.

Online attendees, who had been maintaining a lively discussion on our Zoom webinar, missed the final few minutes of Dr Craig’s talk, since the entire library and indeed much of the university campus temporarily lost power (!). I’m very grateful to our team members Dr Matthew Sangster and Isla Macfarlane for managing the tech side of things on the day, and for remaining calm in the face of this unfortunate turn of events.

In-person attendees, at least, were able to continue with us and were treated to a concluding talk from Dr Dahlia Porter, who has kindly offered to make her piece available in written form on this website in due course. Dr Porter’s talk put the Glasgow library records in dialogue with borrowing records from other parts of the institution, notably the register used for borrowing anatomical preparations. And while we tend to look to look beyond such records for what they can tell us about the past, Dr Porter provided a salutary emphasis on the registers as material objects: complex physical artefacts that signify in their own right.

For the second part of the day, and following some well-earned tea and coffee, we moved from the seminar room into the main reading room at Special Collections, where in-person guests got to see some of the eighteenth-century books and borrowing records up close. Neatly following on from Dr Porter’s talk, this was an opportunity for us all to encounter the borrowing ledgers as (beautiful, fragile) material objects, a sense that can go missing when working with digitisations.

The ‘Books and Borrowing’ team had done some homework on individual holdings that we know to have circulated in the eighteenth century and were able to illuminate them for guests and fellow team members. Aside from the borrowing ledgers, some of the highlights here were a 1759 second edition of Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments, a volume of Charles Rollin’s incredibly popular Ancient History featuring naughty marginalia (with ‘eloquence’ scored out in his title of ‘Professor of Eloquence’), and an abridgement of Philosophical Transactions, arguably the world’s first scientific journal. The showstopper, however, was a 1731 volume of Mark Catesby’s The Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands in massive crown folio, with stunningly executed plates, marking the more opulent side of eighteenth-century book history.

Mark Catesby, Willow Oak and Largest White Bill’d Woodpecker (1731), https://wellcomecollection.org/works/rfsttga7, CC-BY-4.0.

Thanks to everyone involved. None of this would have been possible without the generous support and collaboration of our partners at Glasgow University Library – special thanks go to Siobhan Convery and Robert MacLean for making the event happen.

[1] See also Matthew Sangster, Karen Baston, Brian Aitken, ‘Reconstructing Student Reading Habits in Eighteenth-Century Glasgow: Enlightenment Systems and Digital Reconfigurations’, Eighteenth-Century Studies, 54.4 (2021): 935-55. doi:10.1353/ecs.2021.0098