Rebellion, Enlightenment and Rollin

The commonplace narratives of Scottish history tell us that, in the late 1740s and early 1750s, the nation was reckoning with the aftermath of an unsuccessful Jacobite rebellion and laying the groundwork for an economic boom that, by the 1780s, would have transformed Scotland into a modern imperial power. This era was accompanied by a climate of intellectual enquiry fostering some of the most influential political, philosophical and scientific interventions of the eighteenth century – the Scottish Enlightenment – not to mention a flourishing associational culture predicated in institutions such as debating clubs, scholarly societies and of course libraries.

A page from St Andrews Receipt Book 1748-1753 (UYLY205/2).

Needless to say, beneath such broad brushstrokes lies a far messier historical reality. With an aspect of that reality in mind, it is a pleasure to report that initial work has been completed on the first University of St Andrews borrowing register targeted by the project, specifically (in the institution’s own terminology) the ‘Receipt Book’ covering 1748-1753. This ledger contains a combination of faculty and student borrowings, and in total contains just shy of four thousand recorded borrowings, constituting a significant slice of data that, on its own, is more than capable of offering meaningful insights into the literary culture of mid eighteenth-century Scotland. Still, this will ultimately form only a small fraction of the dataset assembled in the ‘Books and Borrowing’ database.

When in 1826 a Royal Commission was established to report on the condition and operation of universities in Scotland, one of the longstanding complaints discovered in regard to the library at St. Andrews concerned professors holding on to books for years at a time. This issue occasionally creates problems in identifying return dates. More generally, the professors tend to be less punctilious in their record keeping than the students beneath them, who were required to borrow books ‘on order’ using the authority of their teachers. An exception to this rule is John Craigie of Dumbarnie, scion of an influential Perthshire family and possessed of thrillingly clumsy handwriting. The ‘lad o’ pairts’ view of education in this period holds that the Scottish universities were unusually open to students from a range of backgrounds. Still, that the normal library regulations did not (apparently) apply to Craigie suggests the way that class politics interacted with the established academic hierarchies of St Andrews.

The borrowings themselves across 1748-53 provide an insight into the curricula of a Scottish university at mid-century. Among the most frequently borrowed holdings are a 20-vol Universal History, from the Earliest Account of Time (1747-8); a 14-vol set of Charles Rollin’s Ancient History of the Egyptians, Carthaginians, Assyrians, Babylonians, Medes and Persians, Macedonians, and Greeks (dated to 1736 in the library catalogue but probably a composite edition); and Paul Rapin de Thoyras’s 15-vol History of England, as well Ecclesiastical as Civil (1726-31). This emphasis on (notionally) comprehensive survey works tallies with borrowing patterns at the University of Glasgow in the years immediately following and tends to support Seth Rudy’s argument in Literature and Encyclopedism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2014) that the eighteenth century’s knowledge economy was constituted around the pursuit of various forms of ‘complete knowledge’.

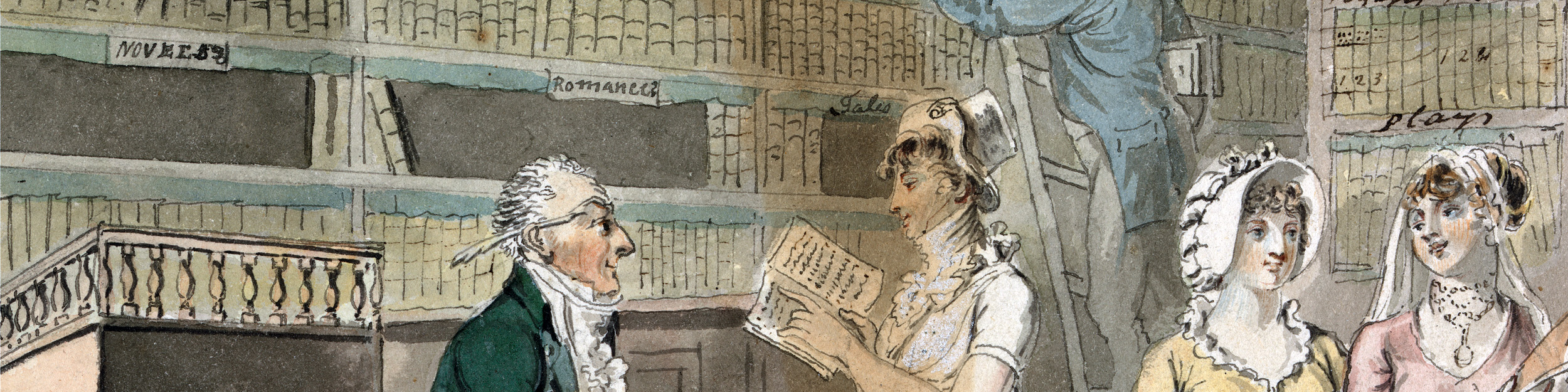

These works formed part of a miscellaneous diet that takes in classical literature, whether in the original or in translation; works of eighteenth-century natural theology such as William Derham’s superbly titled Physico-Theology and Astro-Theology (most likely the 1737 ninth and 1738 seventh editions respectively); the totemic achievements of pre-Reformation and Reformation divinity including a confusing ten-volume portmanteau of Geneva editions of Calvin’s biblical commentaries; and periodicals from The Spectator’s archetypal polite rhetoric to scholarly digests like the Bibliothèque raisonnée. What we now think of as ‘imaginative’ literature is also well-represented: English translations of plays by Molière and Terence are very popular, while in novels, Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones (1749), Samuel Richardson’s Pamela (originally 1740, though being read here in a 1741 edition) and Smollett’s Roderick Random (1748) are unsurprisingly favoured.

Among the knottier questions the ‘Books and Borrowing’ database may be able to shed some light on is the relationship between scholarly reading – whether institutionally or privately directed – and tastes in literary diversion. Frequent clusters of texts across the long term, and contiguous borrowings in general, are promising in this regard. Certainly the impression of these early St Andrews borrowings is that the generic boundary between serious and unserious literature, or between ‘use’ and ‘delight’, obtained quite provisionally. Literary history tells us that in the latter end of our project timeline, the early nineteenth century will see the invention of ‘literature’ in its modern, idealised and aesthetic sense. But we need to reckon with an enduring possibility that different kinds of text – historical narrative and narrative fiction, for example – were being accessed in unpredictable and even potentially identical ways.